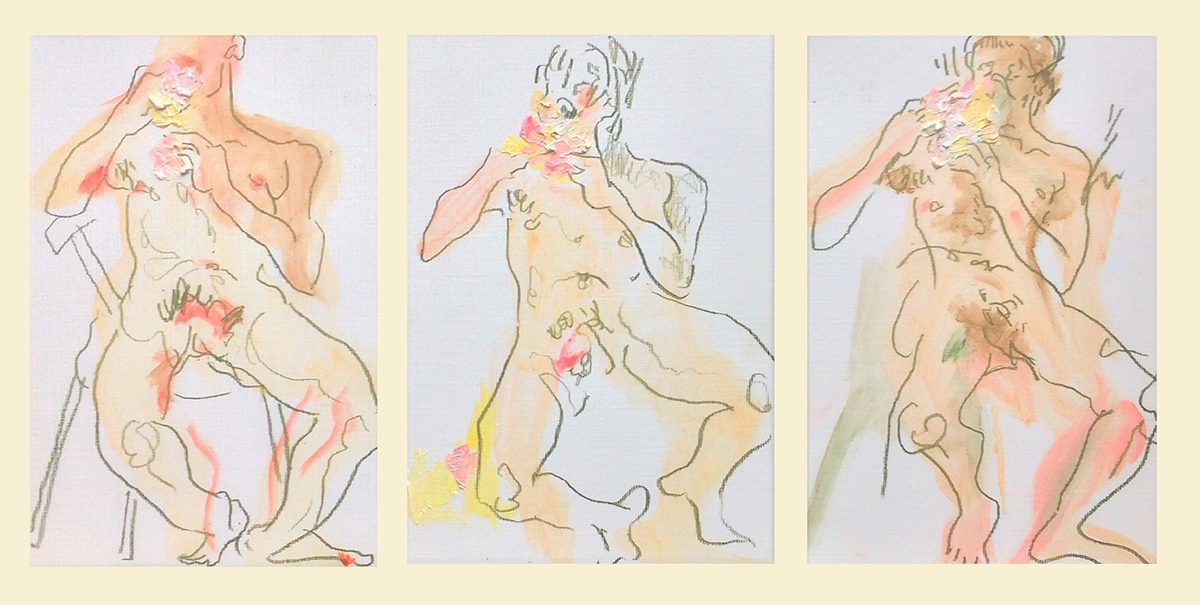

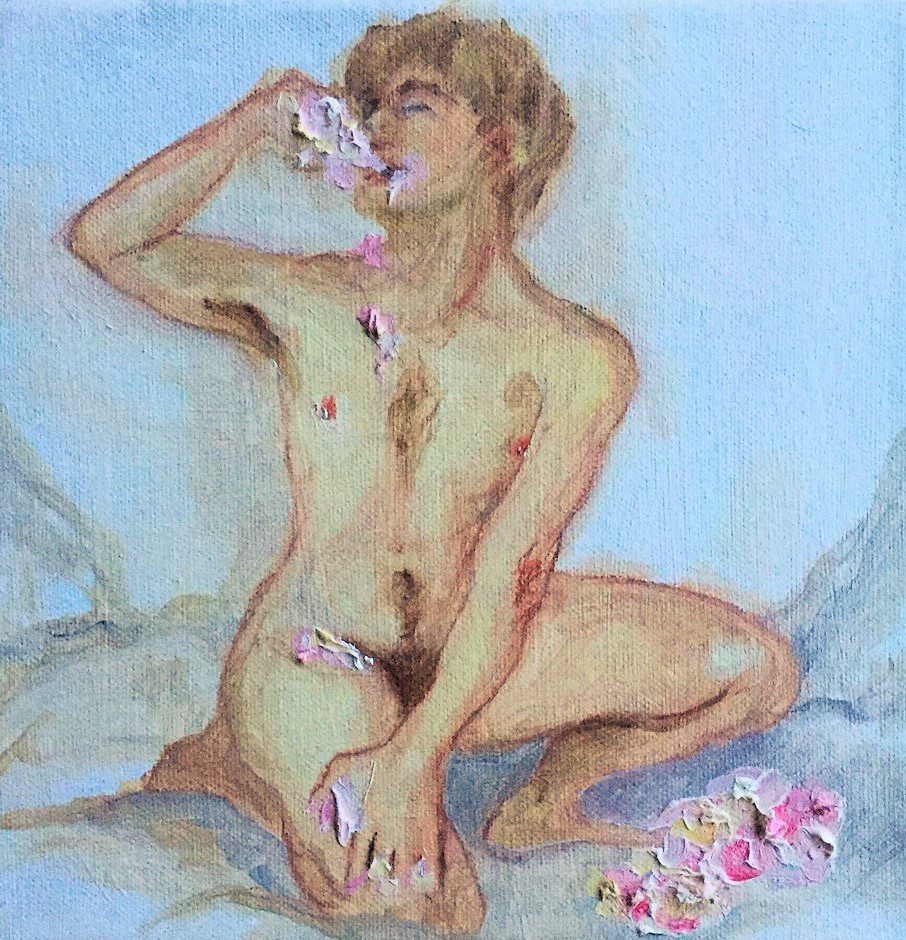

‘Male Nude Eating Cake’ by Georgiana Wilson

Whilst the female body is a commonplace subject in art and historical discussion, representations of the male body remain limited. Artist Georgiana Wilson discusses the troubling stereotypes cast by the classical male nude

This month, the Royal Academy opened an exhibition of Renaissance nudes that plays up to the current zeitgeist by showing equal numbers of naked males and females. In any large European collection of figurative paintings, the Uffizi Gallery or the National Gallery for instance, one would expect to find rooms full of female nudes, their reclining, smooth bodies without pubic hair and arranged for the male gaze. Feminist activists and art historians have persisted in challenging this discrepancy in the European art canon through academic debate (Griselda Pollock, 1970s), public protest (the Guerrilla Girls, 1980s) and even physical attack (suffragette Mary Richardson in 1914), confronting the female body under the male gaze.

If you walk through such a gallery looking for a vulnerable, male body laid bare in the same fashion as the painted women, you won’t find one. Female genitalia are accurately depicted at least 13 times in the National Gallery’s collection of paintings, but you will see only 3 penises. Similarly, exhibitions, books and essays focusing on the male nude are rare in comparison to the thousands dealing with the female body in art. Why has the female body been given so much attention whilst the male body remains almost unscrutinised in art-historical discussion?

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

Perhaps men have not been painted unclothed because until now the patriarchy has stood largely uncontested in the Western world; there has been no call to analyse its presence in painting, whereas from the 1970s the feminist movement has invested in re-examining the female nude. The male body in the history of painting does not appear to have changed much. What one does find on a long walk through the National Gallery are countless heroic, statuesque men in active poses (far from the trope of the passive reclining women) with drapery covering their genitals.

Even when these male bodies are depicted as broken or weakened, for example in paintings of the crucifixion, Pietas, Gericault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa’ or St Sebastian pierced by arrows, they all share a kind of autonomy that commands our gaze. These ‘broken’ men groan or sigh in pain whether we look at them or not, whereas the countless unclothed women rely on the (male) gaze for completion.

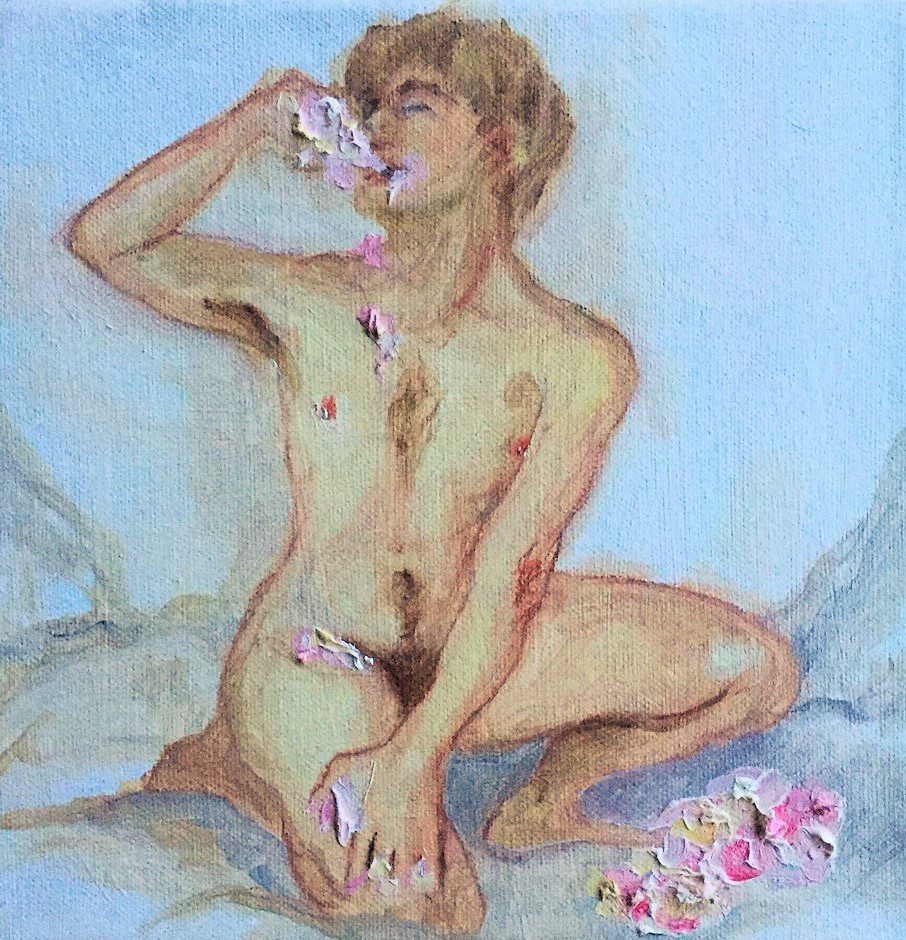

‘Meringues’ by Georgiana Wilson

The gendered tropes of European painting reveal a lot about how our societal expectations for men and women have evolved and I find what we see in the history of the nude disturbing. I would like to draw a link between the heroic, powerful modes in which men have been repeatedly painted and the societal pressures for men to present themselves as invulnerable and ‘masculine’. I believe that a form of this prejudice still exists, with damaging effects that can be recognised in all walks of public life, most troublingly in mental health statistics. The finding from the Mental Health Foundation that suicide is the single largest killer for men under 45 in the United Kingdom demonstrates what is at stake when we think about our societal perceptions of masculinity; this restricting perception can be traced through the history of the male nude.

To understand why the male body has been depicted in such an unchanging manner throughout centuries of painting one must look at the influence of the art academies across Europe, artist run organisations that proliferated from the 17th century, whose aim was to improve the professional standing of artists and provide teaching. The Royal Academy in London is a prime example, a prestigious benchmark of the established art world since it was founded in 1768. The practise, revered since the time of the Renaissance, of painting nudes from first plaster casts of antique statues and then posed models was adopted by the Academies, making the life class central to artistic training.

But why has the female nude persisted as the subject of choice when across all the European academies, with the exception of England, female models were not hired until the 19th century, because of the fear of ‘indecency’ (that they might be prostitutes). Since only male models were hired to pose in academy life classes, it is surprising that the male nude hasn’t been explored in more nuanced ways. The type of body that the academies chose for the life classes certainly has something to do with it; soldiers or boxers that resembled the marble heroes of Ancient Greece were picked to model for drawing classes, harking back to the classical ideal upheld by Michelangelo, Raphael and Rubens. In 1808 a group of academicians actually held boxing matches beside the Parthenon Marbles, forging a link between the classical past and contemporary ideals of virile masculinity.

Read more: PalaisPopulaire & Berlin’s Cultural Revolution

Choosing muscular models who recreated the poses of antique sculpture came to acquire a moral connotation in the European academies. Since the mid-18th century, Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s writings that associated the strong, masculine Greek body with virtue and democracy had hugely influenced the conservative art of the academies as well as antiquarian scholarship. This preference for the classical male nude can explain why the naked male body has been depicted in such a rigid manner since the Renaissance: it set a paradigm of heroic masculinity and a conservative, moralising standard for contemporary male viewers.

There is another aspect of the male nude that has remained the same for centuries: it is still comparatively rare and shocking to find a penis in an art gallery. By the end of the nineteenth century in Britain, as women were being allowed to attend academy life classes, unease over the idea of a naked man posing meant that the model was required to wear bathing drawers, then wind nine feet of fabric around them, and finally secure the whole outfit with a belt for maximum concealment. This Victorian prudery was mirrored in the ‘fig leaf campaign’, whereby male statues’ genitals were covered up. A custom-made plaster fig leaf had to be placed on the cast of Michaelangelo’s ‘David’ when it was given to Queen Victoria in 1857, to ‘spare the blushes of visiting female dignitaries,’ according to a curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum. After this, the male nude was censored.

By the 19th century the unclothed male body had become taboo in Europe for its potential to overexcite or shock (female) viewers. I don’t think we’ve progressed far from this. Despite the fact our ‘period eyes’ (M. Baxandall) have become used to the naked female form in mainstream image culture, in the context of an art gallery, pictures featuring male genitalia are still controversial. This was illustrated by an exhibition in Vienna, Naked Men (2012) that presented modern artworks depicting the naked male form. Ironically, the exhibition’s poster, featuring three naked footballers (by Pierre and Gilles) had to be suppressed before the show had even opened. Even recently, a series of advertisements for the centennial show of Egon Schiele’s graphically contorted, erotic self-portraits were censored on Facebook and had to be covered up in public spaces in Berlin and London. ‘The paradox is that we think we live in a very liberated society but the male nude still troubles people,’ said Xavier Rey, a curator of Masculine / Masculine, a Musée D’Orsay exhibition in 2013 that also displayed images of the male body from the 18th century to the present.

It is worth acknowledging another development that has subverted the male nude: outside the conservatism of the European Academies, queer artists were depicting men in intimate, tender and challenging ways. But these works were viewed as marginal and thus had little influence on the 19-20th century mainstream art establishment in Europe. I would argue that such artists are still disregarded. Robert Mapplethorpe was the first artist to exhibit an image of male genitalia in 1977 in a gallery. His nude and BDSM photos of oiled, flexed muscles and submissive male bodies in leather and chains aggressively confronted the viewer’s perceptions of masculinity and sex, but these portfolios are still viewed as ‘obscene’ and ‘on the edge’, despite their hundred-thousand- pound price tags. Other queer artists such as David Hockney have tried presenting the male body as more tender and vulnerable; Hockney’s most famous LA poolside landscapes of flat, bright colour engulf the nude body, distanced in a picture space that curtails any sense of intimacy for the viewer. If artists like Hockney and Mapplethorpe have tried and succeeded in the past, why has the mainstream subject of the male body remained so conservative that a full-frontal male nude in a painting is still considered surprising? Is it because of sexual politics?

Read more: Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing on redefining Parisian glamour

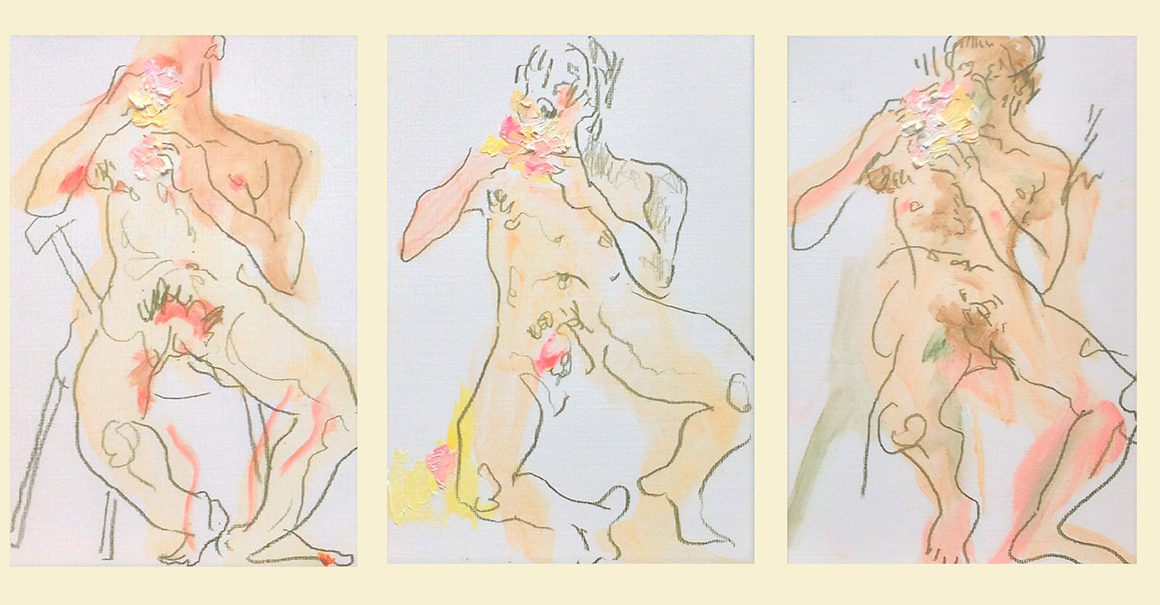

‘Pillowed’ by Georgiana Wilson

We are not used to the vulnerable, naked male body because we do not expect to see men as defenceless or passive. These roles are more normally filled by women: the trope of the ‘Venus Pudica’ as old as Ancient Greece, Titian’s many Venuses, prettily laid out for the viewer’s sensual pleasure on silk cushions, and the commodified women’s bodies of 20th century advertising. What does this say about our ‘Western’, that is Central European, English-speaking society’s definition of gender? Surely today, in our progressive society, when the categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ are supposed to be moving towards increasingly fluid and non-binary definitions, we should be comfortable with the concept of a, dare I say, ‘feminine’ man? The way in which men are depicted in painting can reveal a lot of our societal prejudices about masculinity, because those very pictures have been shaped by social prejudice.

Today, the heroic male bodies of 19th century painting have been replaced by the trope of the ‘anti-heroic’, fleshy man; Lucian Freud’s portraits of Leigh Bowery and Ron Mueck’s hyperreal sculptures are instances of this. Many of Freud’s male nudes are almost forensically repellent: he scrutinised his subjects intensely until they became as dehumanised as pieces of meat. Ron Mueck’s exaggeratedly detailed sculptures of naked men, scaled up or down, also expose their imperfect physicality, with every enlarged pore or microscopic line of hairs producing discomfiture.

These artists paint a bleak picture of contemporary masculinity, but it is also a prescriptive one in which the strong male body has been displaced in favour of a species of emasculation. Whereas in Western society women are ‘allowed’ to be openly weak, to cry, self-scrutinise and admit vulnerability, men are not. But thanks to Rachel Maclean, Tracey Emin and Cindy Sherman female bodies in art have developed beyond the passive, reclining, hairless trope of the past, into a polymorphous range: powerful, confident, undignified and even funny.

I have argued that the new trope of the un-male male body in art reveals a startling truth about our discomfort towards vulnerability in men. CALM charity, which works on male mental health, states on their website that, ‘we believe that there is a cultural barrier preventing men from seeking help as they are expected to be in control at all times, and failure to be seen as such equates to weakness and a loss of masculinity.’ If we cannot produce and comfortably consume art that depicts tender, powerless male bodies, then we cannot readily conceive of a man as anything other than the invulnerable ‘ideal’ of ‘masculine’ that has, until now, been taken for the norm.

To view more of Georgiana’s artworks, follow her on Instagram @georg.kitty

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

Recent Comments