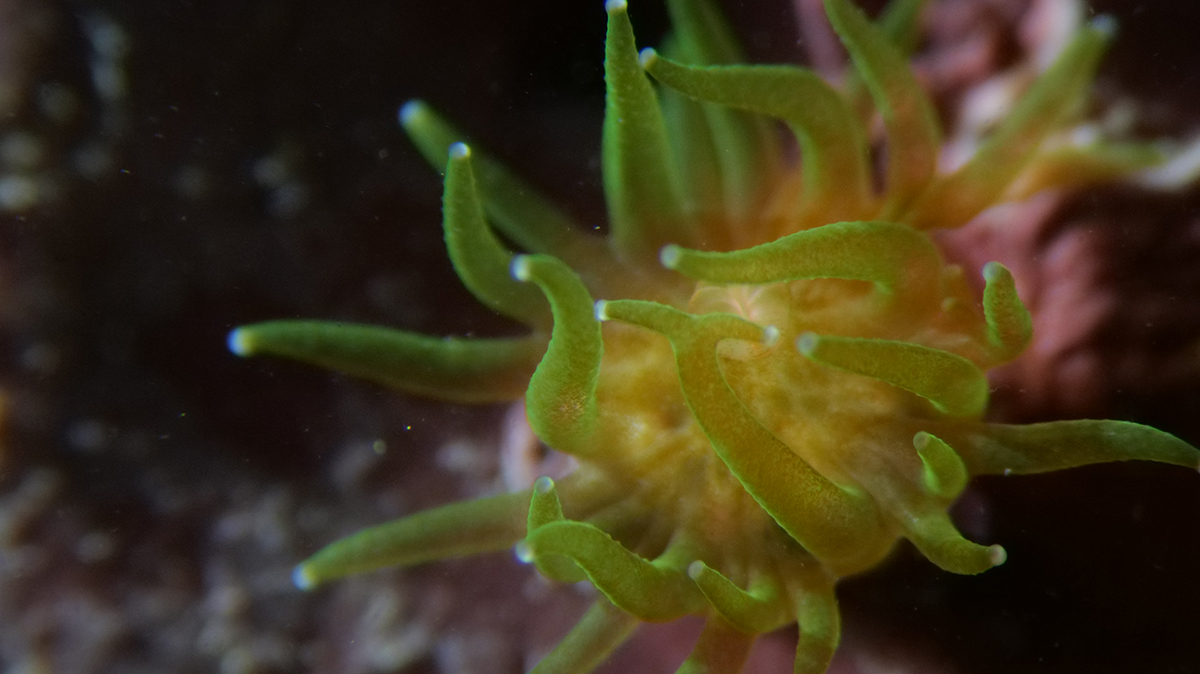

Baby pillar coral, being bred in quarantine, at six months. Image by Kristen Marhaver

She is one of the most compelling figures in ocean conservation. Kristen Marhaver, a marine biologist and TED and WEF star, has made coral regeneration sexy. She tells Darius Sanai that rapid scientific advance and philanthropic support are combining to make the idea of regrowing the world’s coral a real prospect

DEUTSCHE BANK WEALTH MANAGEMENT x LUX

Kristen Marhaver. Image by Bret Hartman.

LUX: Why has there been so much positive progress in coral science recently?

Kristen Marhaver: For a long time, nobody knew how corals reproduced. We assumed most corals spat out little swimming baby corals. It was only around 30 or 40 years ago that mass spawning of corals was discovered and that’s because it only happened a few nights a year. If you’re in the water one hour too late or two days too early, you won’t ever see it. We always had in the back of our minds that the more we understood about reproduction, the more we could help promote coral reproduction in the wild.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

When I started my research career, we would watch corals reproduce and collect their eggs and raise them through the first couple of days or weeks of life and that was it. It was extraordinarily difficult to make progress and most of the coral community thought that there was no way that this would ever lead to something you could apply in conservation. All of a sudden, things just started to click and every year we made a little bit more progress – by “we” I mean the hundreds of people around the world working on a thousand coral projects every year – and decoding one more puzzle at a time and getting a little bit further along the path.

Then we realised all of a sudden something that had seemed impossible became fairly possible. Now everything is aligned just right, and there is this gold rush in coral reproduction science to increase the efficiency of their breeding. We know that every year we’re only going to make a couple of steps more before we have to wait 11 months to try again.

It has been exciting to see the field’s potential grow in the past few years, and it makes it even more exciting to dig into the ever more difficult puzzles because we know that the more we solve, the more we can hand over the answers to other groups that can scale it up from there.

LUX: Is it correct to say there is hope that coral reefs can be rebuilt?

Kristen Marhaver: We are slowly accepting that it’s an option, but we are always really careful about the scale and the timeline when we talk about it. Sometimes I think that we are in year 40 of a 200 year project. So, we can’t go and give an island nation an entire new coral reef, but we can grow a handful of species, get them out in the water, give them 10 years, and they will be the size of basketballs. We can do that on a metres to tens of metres to hundreds of metres scale, but it is also true that the more that people get good at this, and the more innovation is applied, the more it will scale up. In the next five to ten years, we will have changed from saying, “this is something we can do” to “this is something that we can scale up confidently”. There is an analogy with orchids. These used to be extraordinarily expensive, but if you go to a supermarket or a florist, you will see an orchid for $10. The reason they are so abundant and cheap is because scientists figured out meristem culture, so instead of waiting for orchids to grow big and then dividing, they just take a tiny sliver of tissue and grow a whole new orchid. That completely changed the availability and propagation of those plants. We are about to see the same kind of thing in coral propagation.”

Juvenile corals, aged 18 months in the aquarium system at CARMABI. Image by Kristen Marahver

LUX: You can recreate coral killed by human activity, but how do you ensure the new coral won’t be killed again?

Kristen Marhaver: That’s a great question. And it’s a huge concern. We have a couple of reasons to be optimistic, one of which is that there’s now a really powerful race amongst the countries to enact not only climate plans, but also marine protected areas and fisheries regulations and sewage system modernisation. There are also some pretty nice examples of places where juvenile corals can do better than the adults could. That’s partly because when we are growing juveniles, there is a tremendous amount of genetic diversity. You have more chances of getting a good hand by putting 20,000 juveniles of all different genetic combinations into a place, as opposed to fragmenting 10 or 20 adults and gluing those pieces back onto a reef.

Read more: How Chelsea Barracks is celebrating contemporary British craft

LUX: You are passionate about making sure philanthropists support the right groups in coral restoration.

Kristen Marhaver: The most powerful groups in coral restoration are in places like Belize and the Dominican Republic and the Philippines. You don’t necessarily hear about them because they don’t have the glossy brochure and the advertising budget and the social media person; they’re just all underwater busting their butts. It is really important to find a group that’s not just flashy and well branded, but one that is honest about what they can do. It’s important for donors and philanthropists to do their homework and find out what’s going on behind the scenes.

LUX: And why is coral important?

Kristen Marhaver: I was interviewed once on a television station and the interviewer asked me why we should care about coral reefs. And I said, “Well, they bring in tourism money, and provide food for a billion people around the world, and they grow these beautiful structures that are art.” Then he asked, “Why should we care?” I said, “If you don’t like money or tourism or art, then I really don’t know what I’m going tell you.” But if you have ever been to a beach in the tropics, or been in a building in the tropics, you may have corals to thank for keeping that beach there, keeping that building up. It’s also cultural heritage, the same way that we care about losing languages or losing monuments or losing art. It’s because it’s the heritage of our earth and the cultures on earth. We owe it to small communities around the world to help them hold on to that cultural value as well.

Dr Kristen Marhaver is a coral reef biologist at the Research Station Carmabi and the founder of Marharver Lab, both in Curaçao.

Find out more: researchstationcarmabi.org; marhaverlab.com

This article originally appeared in the LUX x Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Blue Economy Special in the Summer 2020 Issue.

Recent Comments