Sundaram Tagore. Photo by Paul Terrie. Photo courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

Art and culture is part of gallerist Sundaram Tagore’s DNA, coming from one of India’s leading creative families. Here, Tagore speaks to LUX’s Leaders and Philanthropist Editor, Samantha Welsh, about the importance of showcasing underrepresented artists and ensuring creatives are not pigeonholed

LUX: How did your upbringing nurture a fascination for cross-cultural exchange?

Sundaram Tagore: I grew up in a house of art and culture. My father, Suho Tagore, was a painter, poet and writer. He was one of India’s early modernists. He was raised in a family of artists and creative people, including Rabrindranath Tagore, the first non-Westerner to win the Nobel prize for literature. When I was a child, my father was publishing an art magazine, building a museum and organizing exhibitions. We had a constant flow of creative people from all over the world staying in our Calcutta home—artists, writers, and filmmakers. Calcutta, at that time, was a glamorous cosmopolitan city and India’s intellectual capital.

But it goes beyond that. My family has been involved with the idea of cross-cultural exchange going back generations. In the early twentieth century, they built a globally focused university, now known as Visva-Bharati University, outside of Calcutta. They were so committed to the idea, they invested everything—the entire Tagore family fortune, including our ancestral home—to build it.

The school was known for its intensive arts program and an emphasis on returning to nature, with classes often held outside under the trees. By the early 1920’s, there were students coming from every corner of the globe to attend, including notable scholars and artists, including the renowned British painter William Rothenstein. Mahatma Gandhi and disciples were based there for a time.

In 1922, the very first Bauhaus international exhibition, which comprised more than 250 works of European avant-garde art, was brought to Calcutta by my family. The exhibition featured works by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Lionel Ettinger presented alongside work by modern Indian artists.

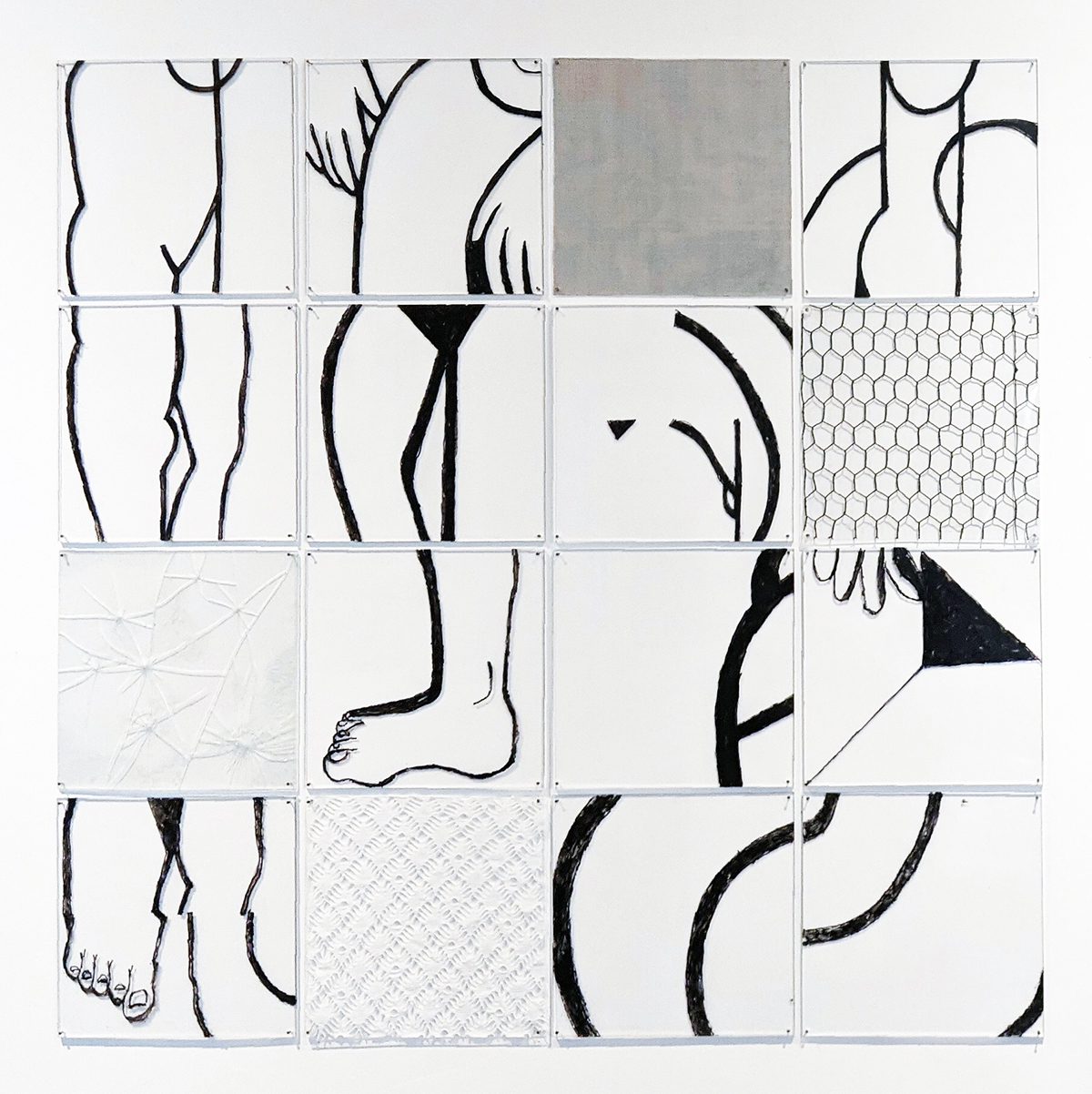

Susan Weil, Landscape, Image courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

LUX: Where did you start to seed these East-West dialogues?

ST: Again, it goes back to my family, who, over generations, created real cultural dialog. My father, who had studied in England in the 1930s, came back to India and formed one of the first arts collectives in India called the Calcutta Group—inspired by the Bloomsbury Group. So, those ideas have always been with me, it’s part of my mental DNA. Rabrindranath Tagore advocated for universalism throughout his life. This was the family ethos.

LUX: A former director of Pace Gallery, NY, how did that experience challenge your perception and change your direction?

ST: I saw a very professional world at Pace. It was a highly aestheticized environment with rigorous programming and curatorial values. Those were the things that I carried with me when I opened my own gallery—paying sharp attention to the details.

LUX: What was your thinking behind launching the flagship gallery?

ST: I came into the gallery world from an academic background. I imagined that I might be a museum curator. I was doing dissertation research at Oxford University on Indian Modernism, again, returning to issues of East-West dialogue and intercultural discourse. It was a topic close to my heart, this question of what modernism means to a deep-rooted traditional culture, such as India’s. To be modern, one has to reject tradition, that is the basis of Modernism. And for many tradition-bound cultures, like India or Indonesia, if you give up those traditions, how do you exist? It’s like choosing to be an orphan.

As a student of Indian Modernism, I soon discovered there were few museums that could accommodate me because in those days, there weren’t many positions in my field of expertise. And so, I began working as an advisor for various museums and institutions. Eventually, I decided to create my own gallery, which opened in 2000 in SoHo, New York.

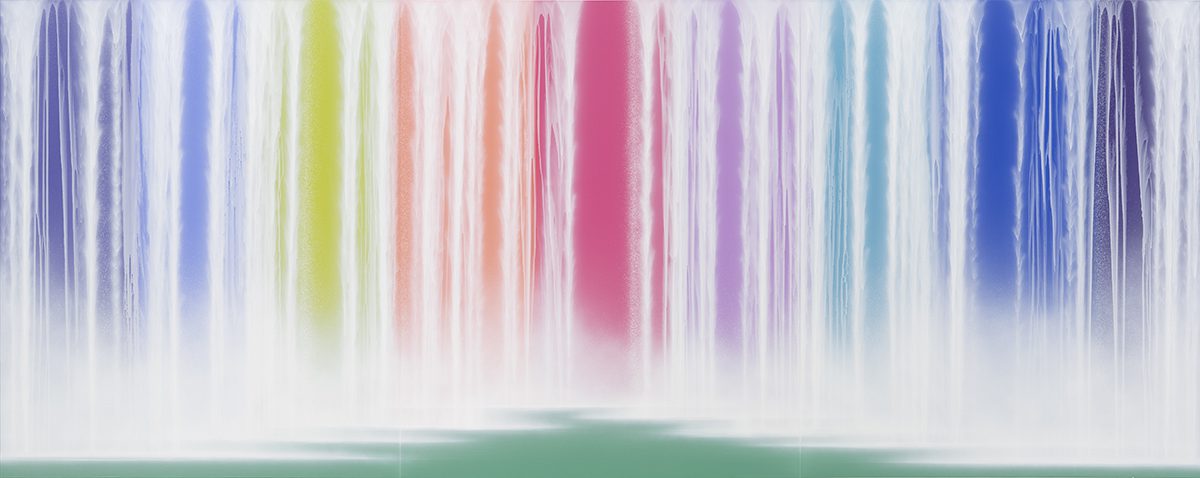

Hiroshi Senju, Waterfall on Colors, 2022. Image courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

The kind of gallery I wanted to visit didn’t exist. At that time, most galleries in New York had a strong Euro-Western focus, representing predominantly men. There were a few galleries representing Indian artists, Russian artists or Chinese artists, but there were no galleries focussing on the global community. I was drawn to artists who synthesized ideas from disparate cultures, drawing from diverse formal traditions and philosophies.

It became my mission to show that some of the best and most meaningful art was being created by artists deeply engaged in cross-cultural explorations. So I assembled a global roster of artists, including Hiroshi Senju, Sohan Qadri, Karen Knorr, Zheng Lu, Susan Weil, Ricardo Mazal and Golnaz Fathi, who crossed cultural and national boundaries. I showed this work alongside important work by overlooked women artists from the New York School, who I always thought deserved more attention and representation. We will be showing an exhibition by Susan Weil (b. 1930, New York), a groundbreaking American artist from the New York School and the first woman I signed to the gallery in 2000 at Cromwell Place in London this October.

This global and inclusive outlook naturally lead to opening international locations, including Beverly Hills, California, in 2007; Hong Kong in 2008; and Singapore in 2012. And just this year, we opened a permanent space in the London arts hub, Cromwell Place.

LUX: What kinds of impact can artists make when you introduce them into cultures where art is under-represented?

ST: Art is always present, everywhere. However, society may not be in a position to appreciate it because of economic or socio-political issues. But people always create. It’s a basic human drive.

Artists challenge us to think differently or see things in new ways. When you bring new or underrepresented artists into a space, they revitalise it, at least creatively.

Sundaram Tagore’s Apartment with interior styling by Philippa Brathwaite. Photo by Paul Terrie. Photo courtesy Sundaram Tagore Gallery

LUX: How would you say this has changed the art scene over the last couple of decades?

ST: By looking at a work of art, appreciating it ,and having a discourse about it, we expand our minds and take those conversations into our everyday lives.

In the past few decades, the art world has expanded in a very significant way. Interest has expanded beyond the United States and Europe in ways we couldn’t have imagined twenty years ago. There are biennales in some of the remotest corners of the world shining a light on artists who have been underrepresented in the art world. Curators and some galleries are now paying attention to artists they wouldn’t have a decade ago. Some of this has been prompted by politics, and now, increasingly, by economics.

Technology has also expanded the commercial art world. We all have more access to information. This is positive.

LUX: Is there a tendency to typecast artists by region, gender, cause, medium, at the risk of restricting their freedom to explore new avenues, genres to reach their fullest potential?

ST: There is a tendency to typecast artists by identity. Religion, gender, ethnicity are easy categories. In the last few years, there’s been a rush to redress past wrongs in the art world when it comes to race and gender in particular. Museums and galleries don’t always get it right, but they’re trying to represent and champion a broader range of artists and are now expected to do better.

One thing I never worry about is artists being restricted in their freedoms or creativity. Artists are by nature rebellious, contrarian, ground-breakers and rule-breakers. Galleries, museums and collectors may be hung up on typecasting, but not artists.

Susan Weil, Untitled, 2022. Image courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

LUX: You are known to immerse yourself in your work, engaging fully with geographies and people. How does that approach align with your beliefs?

ST: Because I travel so much and I’ve lived in a dozen different cities across the globe, geographies dissolve and country, culture and ethnicity are almost irrelevant terms to me. I don’t judge people on their nationality, religion or any other identifier. If I connect with a person, I can be at ease in any space in the world.

LUX: Where would you say art conversations are making a significant impact on society?

ST: Many art-related conversations right now are about marginalization and identity. I think that will go on until we address these issues with broader representation. That’s the nature of art, isn’t it? To push the conversation into the foreground.

Increasingly we see how the role of activism in art can have the real-world impact, especially relating to issues of social justice and environmentalism. For example, we represent the world-renowned Brazilian photographer and activist Sebastião Salgado, who has told the stories of millions of dispossessed people around the world. To that end, he and his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, have a nonprofit, Instituto Terra, which has been devoted to reforestation and environmental education since the 1990s. Their recent collaboration with Sotheby’s—the largest curated solo exhibition of photography in the auction house’s history—raised more than a million dollars for their foundation.

The Salgados have replanted 2.7 million trees in a region previously covered by the Atlantic forest. It was an infertile and burned land where erosion showed the red veins of the earth; the trees, the smell of the sweet flowers, the song of the birds had disappeared. Their efforts, fueled by sale of Salgado’s work, show the power of art and artists to make a difference.

LUX: How will you continue to challenge and change perceptions?

ST: I’m not interested in controversies, trends or provocation. We have enough of that in other arenas today. I want to use art as a vehicle to bring people together.

Find out more: www.sundaramtagore.com

Recent Comments