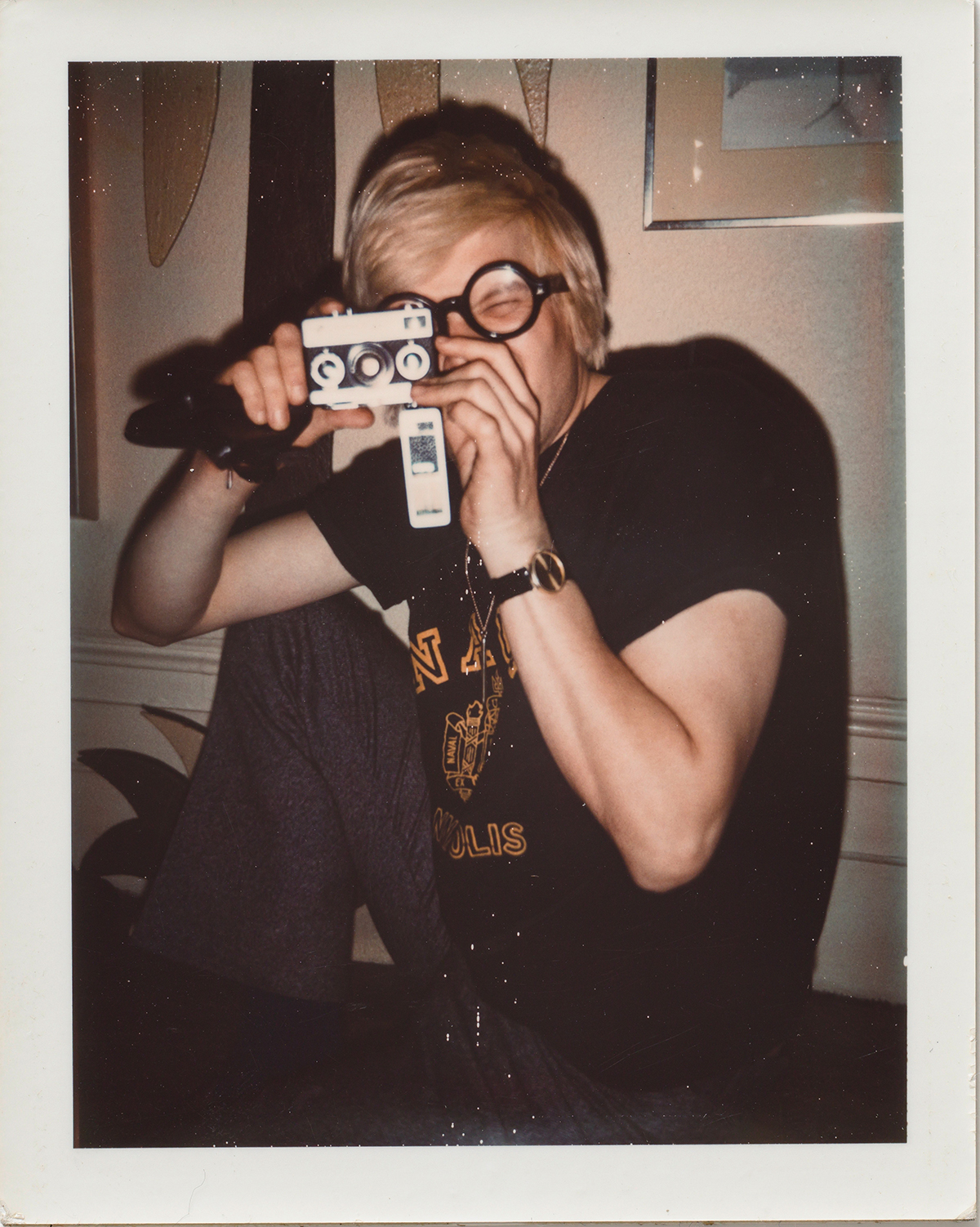

Afshin Naghouni in his studio. Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Born in Iran, visual artist Afshin Naghouni immigrated to London in his mid-twenties where he began to establish a reputation for his imaginative and dynamic artworks that blur the lines between figurative and abstract. Ahead of his upcoming exhibition in January 2021, LUX contributing editor Maryam Eisler visits and photographs the artist in his London studio

Maryam Eisler: So right now, I’m looking at your self-portrait. It’s complex…

Afshin Naghouni: When you do a self-portrait, or any focus on configuration, you tend to go towards the physical features, making sure that it looks like it should do. The moment you go towards abstraction, it becomes about focusing on other things rather than the obvious. A lot of it is conscious or self-conscious. I think a self-portrait needs to be more accurate than straightforward representation.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Maryam Eisler: Yes, I see very few cues about you in the physical sense. Is it difficult to define oneself?

Afshin Naghouni: It is if you think about it; I don’t think about it much. When I was doing it I just thought: this is me painting my inner being. I just splattered myself all over the canvas trying to think about what I am and most importantly what I am not!

Maryam Eisler: Yes, it looks like you splattered your guts! Talk to me about the reality of the last five months for you; this period of confinement and self-isolation. How have ‘Covidian times’ affected your mind, and your psyche ?

Afshin Naghouni: For me, the only direct consequence is that I have not been able to paint. Of course, I’ve doodled around at home, but nothing can replace the air in this place [the studio]. I just love it. Sometimes I don’t even paint; I just sit around, I listen to music and I breathe the air. So not being able to come to the studio for me was difficult. So what did I do instead? Well, I painted in my head, cut off from the outside world!

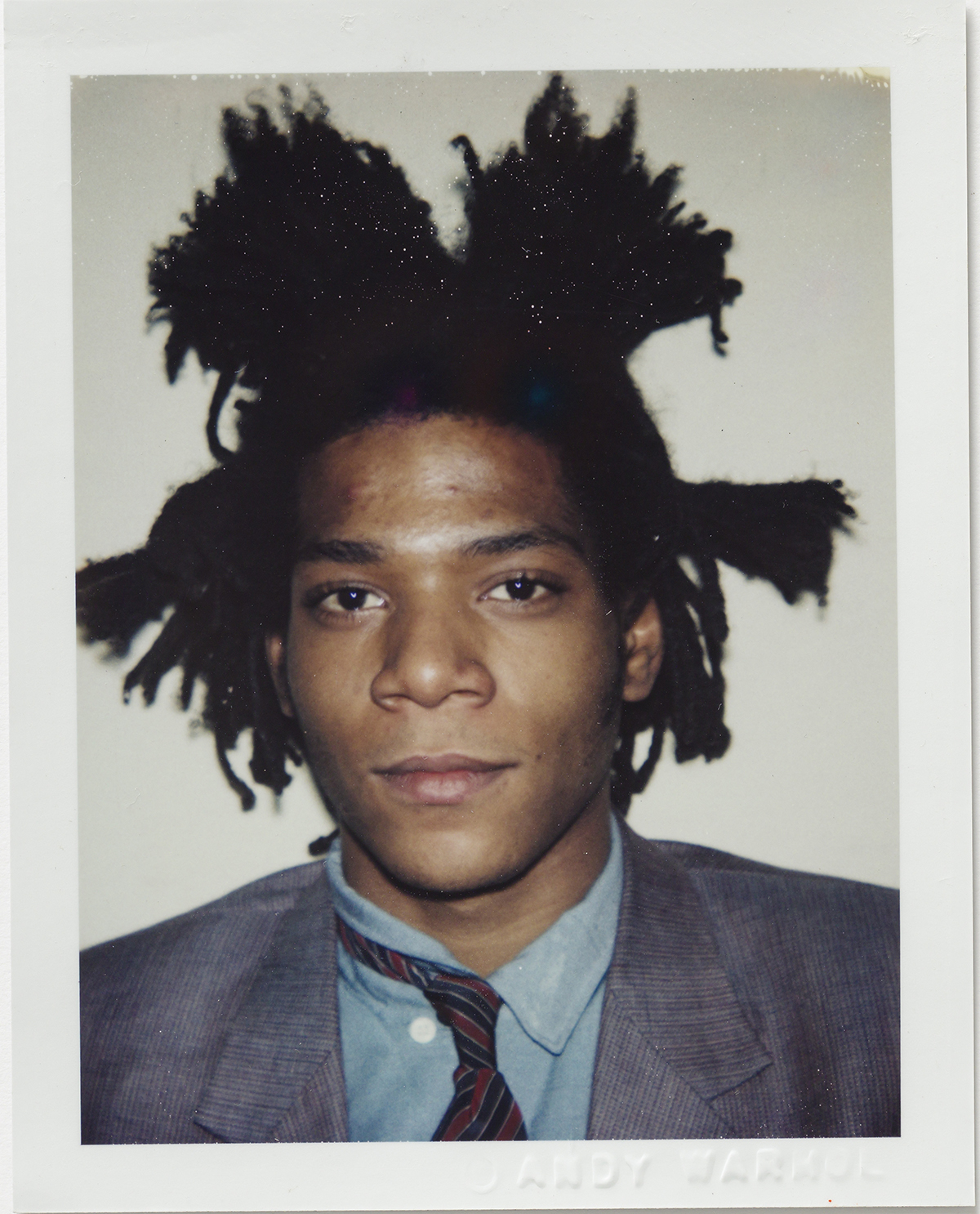

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: What do you mean by ‘painting in your head’?

Afshin Naghouni: It becomes a race between what I can bring into my head and what goes onto the canvas. My mind is always way ahead of me, and I am constantly trying to catch up. When it happens, it is exciting. because you can’t stop and it becomes more physical, the application and all that. The other thing that can happen, of course, is that you haven’t figured anything out and you just want to paint. It becomes a slur because you can be ahead of your thoughts on the canvas, and you need to come back, have a cigarette, have a coffee, and try to figure out what you are trying to do. They are both equally exciting and challenging. Well, not challenging; painting is not hard. The hardest thing is just trying to keep working, and stay motivated.

Untitled #6 (2017), mixed media on canvas 150×120 cm from Afshin Naghouni’s Nostalgia & Reminiscence series

Maryam Eisler: Have you managed to remain motivated during the last few months?

Afshin Naghouni: During this whole period, I have been desperate to work. I only went out for essentials for four months. My issue is that I like people. I am a social creature. I need to have human contact and connection, and a lot of it. So, not having been able to come here [into the studio], to work and see friends, has been very difficult.

Maryam Eisler: But has it also afforded you the gift of time?

Afshin Naghouni: I have had the time to slow down. To kind of bring together all my thoughts and to reflect on the things that are moving me forward. My struggles are more conceptual in nature. For example, I have never been a great fan of abstract painting and that is primarily because I have fundamental problems with modernism, and what it stands for in its essence.

Read more: Why do we act the worst with those we love the most?

Maryam Eisler: What are those problems?

Afshin Naghouni: I find modernism just like [Clement] Greenberg did: elitist, sexist, inaccessible. I am not saying that art has to be accessible, but today, I am personally focused on form, movement, rhythm and the attempt to breathe emotion into the canvas. In the past, I would start with abstract forms on the canvas and I would gradually work my way to make it representational. I think I am going backwards now. I find that reverse process interesting and exciting. I want to create overall compositions filled with life and energy, paintings that are visually engaging, playful and experimental.

I don’t care if it’s done before one way or another. We are at a point where not much is left undone. I pinch, borrow and steal from those before me, to make things work, to empty my guts on the canvas, and then I use my knowledge to polish it. I really don’t know if it’s any good and to be honest I’m too old to overthink it.

Maryam Eisler: Is that not part of the artist’s journey?

Afshin Naghouni: I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and about why I’m doing what I’m doing – trying to make sense of it in my own head. The truth (whatever that is) is that I am sick and tired of identity-centred, self-obsessed art; art that sacrifices a great deal in order to cement the artist’s place as Middle Eastern, African, female, LGBTQ etc; art that identifies the person with everything under the sun, except for being an artist; art focused on addressing something seemingly so profound that it ceases to be art – all that self-obsessed, self-indulgent, pretentious pile of shit that crawls up gallery walls!

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: How about art-driven identity instead of identity-driven art?

Afshin Naghouni: Ah! The art market is such a precarious thing and it has been for such a long time. I do not pander to it much. You have to, first and foremost, please yourself, present yourself I guess. It takes courage to move in different directions and it takes conviction. The truth is that I get bored! I cannot sit down and do the same thing for years on end even if I know my collector base likes certain types of my paintings. I don’t want to leave any what ifs… So I am experimenting all the time.

Maryam Eisler: How many paintings do you trash?

Afshin Naghouni: [Laughs] I do not trash. I do not burn. I just put aside.

Maryam Eisler: Who amongst art historical figures has affected you the most?

Afshin Naghouni: Picasso.

Read more: Artnet’s Sophie Neuendorf’s guide to shopping for art online

Maryam Eisler: What is it about Picasso‘s work that appeals to you?

Afshin Naghouni: His carefreeness, I think.

Maryam Eisler: Is there one of his paintings in particular that comes to mind?

Afshin Naghouni: I will always be in love of his analytic period, but I am also very much enjoying the paintings he did of his lover Marie Therese around 1932-33. I love the freedom of application and the loose strokes, childish, free and sensuous at the same time.

Maryam Eisler: Who else inspires you?

Afshin Naghouni: [Anselm] Kiefer, Cecily Brown, Caravaggio.

Maryam Eisler: What is it about Kiefer’s work?

Afshin Naghouni: The sheer scale, and his ability to achieve such amazing compositions within that scale. He is one of those few artists who has found the perfect balance between form and concept.

Nostalgia (2017), mixed media on canvas 160×200 cm from Afshin Naghouni’s Nostalgia & Reminiscence series

Maryam Eisler: Is that something you are striving for?

Afshin Naghouni: I am still trying to find that balance. Now I do not pay that much attention to concept any more; I focus on form instead. I find it exciting, it gives me energy to think about the things I want to do.

Maryam Eisler: What are you reading right now?

Afshin Naghouni: I am reading The Art of Creative Thinking by Rod Judkins. The author is a Central St Martins graduate. You do not have to be an artist to be creative. Everybody is born with creative genes. They just get suppressed by life events. I’m also reading Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, but it kind of depresses me.

Maryam Eisler: Why does it depress you?

Afshin Naghouni: The future that Hariri describes is not the kind of society I want to live in.

Maryam Eisler: Do you mean that you like humanity with all its flaws?

Afshin Naghouni: Yes, absolutely. I had this deep and heated conversation with a friend recently, who insisted that art and artists are going to become irrelevant, and that AI is going to create the very best art that art can ever be. But how is that possible? Until AI can get angry, can cry, can fall in love the way that we, as humans, can, it will surely never be able to surpass art created by human hands. Frankly, I would rather not be around when or if AI is ruling the world. It is often our human flaws that add greatness to any artwork.

Untitled #3 (2017), mixed media on canvas 160×200 cm from Afshin Naghouni’s Nostalgia & Reminiscence series

Maryam Eisler: Do you have an overall concept for your upcoming show in January?

Afshin Naghouni: I just want to paint between now and then the way I want to paint, free, without overthinking the process. If I only have five paintings by then, then that will be it.

Maryam Eisler: Talk to me about the courageous choice of colours in your paintings and the energy they exude.

Afshin Naghouni: Those who are familiar with my work know well that it never used to be this colourful. That’s why I say, I feel I have really rediscovered colour. I like and want to play, and if colour is the exciting dimension in the game, then let’s put it to work. I’m also a city boy. I like big cities with all the people that inhabit them. I am in love with London. It is a melting pot of cultures and that in itself is pure colour. The energy in this place is unique. I equally love the countryside, but after two weeks away, I need to return to urban colour.

Maryam Eisler: Finally, I want to talk to you about place. You mentioned that you love London, and urban life. What about the location of this particular studio [in Ladbroke Grove], and the connections that you’ve made with your local community?

Afshin Naghouni: It is amazing. First of all, in this line of arches here, there are mechanics, fashion designers, recording studios, different kinds of professionals working together, next to one another. I know them and they know me. It feels good. I like the walk from here to home and back. I never get tired of the route; everything about it offers me a colourful visual canvas of life in London. When I am going down the road, I just listen to the sounds that accompany me all along, and I feel the energy. I love everything about it. The community around here is also very strong; we try to make things work together all the time. We rely on one another. I really miss that interconnectivity.

Discover more of Afshin Naghouni’s artworks: afshinnaghouni.com

For more information on the artist’s upcoming show at HJ gallery in January 2021 visit: hjartgallery.com

Note: this interview was conducted prior to the UK lockdown in November 2020.

Recent Comments