For a mentor, Jonathan Miller could give some pretty damn terrible advice. It was sometime in the late 1990s, shortly after we had met. I was back in the UK from my first job after university, as a foreign correspondent, and, low on contacts but high on ambition, looking for guidance.

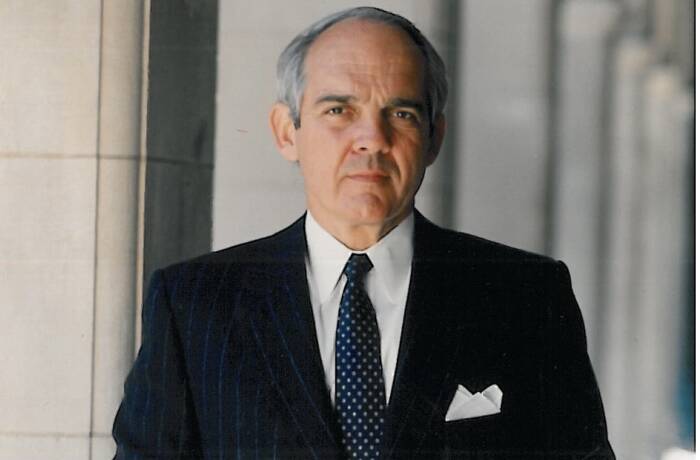

Jonathan, to me, was the perfect role model. Intelligent, hilarious, swashbuckling, iconoclastic, a brilliant writer who was also good enough with people to have become an editor and columnist on what was then an all-powerful national newspaper. He was someone whose words rang out across the country every week, and for no reason other than a bond formed of camaraderie, a mutual dark humour and some hobbies in common, he took me under his wing.

I had heard of a job going, as Rome correspondent of The Guardian. As an Italian speaking Europhile who had studied European politics at Oxford, worked as a foreign correspondent, and written for the Guardian, I felt I was a strong candidate. I asked my new mentor for his advice. “That’s the perfect job for you !” he said, “and you can sock it to those lefties at the Guardian!” Or words to the fact that effect – Jonathan‘s soft right politics were at odds with the newspaper. “Tell them it’s a pivotal time for Italy as it’s going to split into two states, north and south, you can predict it and cover it!”.

It’s true that the Lega Nord, the Northern League, which favoured breaking up the country into its wealthy north and poorer south, was then at its zenith, but he was the only person I had heard to make this prediction with confidence. But he was Jonathan Miller – not only a national newspaper columnist, but one of the most convincing people on the planet.

I applied for the job, letting my (his) prediction for the future of Italy be known. I didn’t even get an interview. I am not sure why, but a friend working at the Guardian did email to ask me why on earth I had predicted in my application that Italy was going to split into two.

‘I always think of Jonathan’s ebullient, slightly dark confidence, whenever I launch a new issue of any publication’

I mentioned this to Jonathan, dolefully, during our next chat at his house. “Oh well it might happen sometime! Have a drink! Now, I’m 40 and I need to buy myself a Menoporsche! Which one shall I get?” With that, the previous topic was forgotten and we delved gleefully, like small boys with a combined age of 65, into the next. (He sold the “Menoporsche”, a glossy black Porsche 911 from the 1990s 964 series, almost as quickly as he purchased it.)

The next “project” we had together was altogether more serious: after an ownership change at the publication we both contributed to, we got together with some other senior editors (who looked askance at the young freelance in the room) and put together an ambitious project for a new London weekly newspaper, a kind of cross between The New Yorker and The New York Observer, then at the height of its subversive influence. We got to the stage of producing dummies, a content plan and a business plan (when I say we: this was 90% Jonathan, 9% his fellow editors, and 1% me) and looking for funding for The Beast, as he titled it. Long evenings were spent at his desktop Mac in Hampstead piecing plans together for this game-changer (this was when confidence in legacy media was still high).

I don’t recall exactly what happened to The Beast; perhaps the hunger to see it through was not there, or the funding proved difficult, or both. But the experience, a crash course in magazine making from people who had done it, taught me hugely important lessons for a future where I did and still do launch and create magazines and media, and I always think of Jonathan’s ebullient, slightly dark confidence, whenever I launch a new issue of any publication.

Those beautiful days when Jonathan lived in a modernist house in Hampstead, and I would ring him up and drop round for tea or lunch or coffee or drinks with him and his delightful wife Terry – surely one of the nicest people ever to work for Goldman Sachs – and his children Alysen and Dan, seem infinitely far away now.

‘Highly intelligent and with the acuity of, well, a top journalist, Jonathan was always active – hyperactive, even’

Soon, I did get a proper job on a national newspaper, thus instantly disappearing my available time to drive up to Hampstead; and the Millers moved, first to the Surrey/Sussex border, from where he wrote an engaging newspaper column about farming on the edge of suburbia, and thence to the Languedoc, in southern France, from where he became a celebrated correspondent for The Spectator and other media.

He gave me a tour of his Languedoc “starter chateau” more than 20 years ago when he was buying it, and to my shame I never visited the completed house, although like millions of others I feel I did, having read his dispatches.

In France, Jonathan embraced his French inner child (having always been very in touch with his British/American/Jewish inner child back in London). According to those who know him best, he inserted himself fully into village life, not only becoming fluent in a second language (something he said improved his writing in English, and should be obligatory for all journalists), but also entering the political arena by being elected to the local town council. He wrote a book about France and frequently contributed provocative, funny, well-informed (and borderline inflammatory) pieces about French politics to both The Spectator and Daily Mail. Emmanuel Macron provided a lot of his material – “the gift that keeps on giving,” he said – but his writing for The Spectator was a potpourri of other subjects that caught his interest, including food, sexual mores and the French health system.

Last year, he decided it was time to write a memoir of his life as a journalist across the changing spectrum of the news. Shock of The News, Confessions of a Troublemaker was finished just before he died. It is typically Jonathan all the way through, insightful, unpredictable, entertaining, iconoclastic, and highly personal, including all his top tips for being a troublemaker, with the primary one being: “read this book!”.

Family was always extremely important to Jonathan: he once sent me an email with the subject field “My brilliant daughter”

My fondest memory of Jonathan, though, is not anything to do with the media or writing. Shortly after we met, he announced that he had tickets for the Iran vs USA match in the World Cup, in France. Jonathan was tickled by the idea of an American Jew and an exiled Iranian Brit going to this match together, and kindly invited me to join his family and other Iranian friends on what remains one of the most fun I have ever had at a football event.

The atmosphere was a party, from both sides of supporters uninterested in higher politics, nobody really cared who won (Iran, I think, 2-1) and we spent 48 hours eating well, chatting about politics and wine and cars and how outrageous various things were that Jonathan disagreed with. Years on, his latest columns dealt with likelihood of a French civil war, which I personally treat with as much scepticism as the prospect of a North and South Italy, but in this case he had more than 20 years of living in the country to back up his views.

Highly intelligent and with the acuity of, well, a top journalist, Jonathan was always active – hyperactive, even – which makes his death even more incomprehensible. He didn’t exactly have joie de vivre – he had too much of the Jewish inner black humour for that – but he had vivre. It would make sense to Jonathan to say that even though I haven’t seen him for 10 years, I really miss him. Farewell to my mentor, his buzzing, flashing lights turned off far too soon.

“Shock of the News: Confessions of a Troublemaker” is available from Waterstones, Abe Books, Amazon and other booksellers

Darius Sanai is owner of LUX Media and The Oxford Review of Books, an Editor-in-Chief at Condé Nast, and in another life, launched The London Beast under Jonathan’s direction