Drawings for Ruinart 2020, by David Shrigley

Glasgow-based artist David Shrigley is best known for his playful and humorous illustrations, which are often accompanied by deadpan captions, commenting on the banality of contemporary life. He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2013, and has had major exhibitions at the likes of London’s Hayward Gallery and Manchester’s Cornerhouse. Here, the artist discusses his creative process, the interaction of language and his latest collaboration with Maison Ruinart

David Shrigley

1. Tell us about your concept for Maison Ruinart?

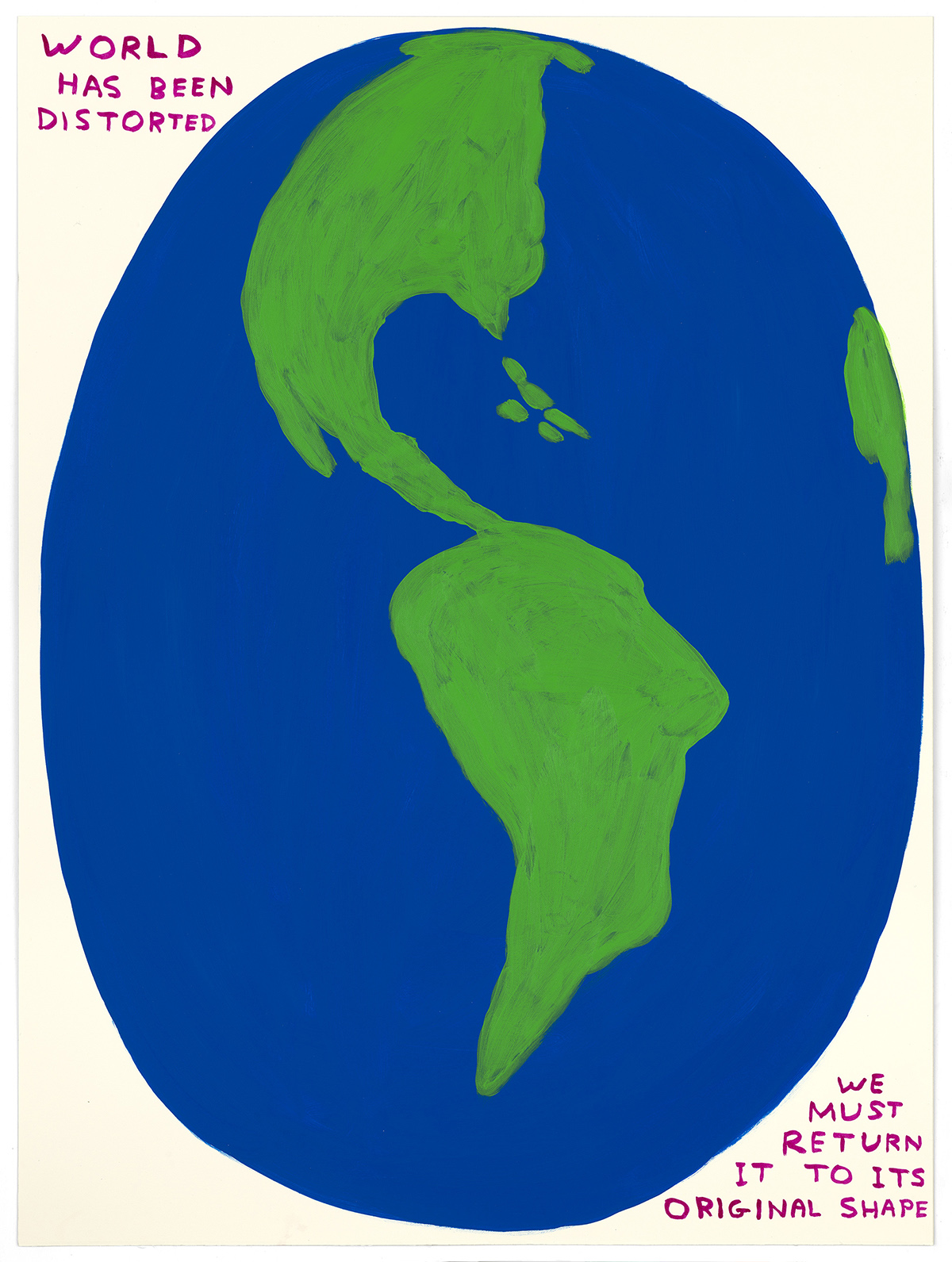

The concept behind ‘Unconventional Bubbles’ is about taking the viewer on an enlightening yet playful journey of champagne production whilst enhancing awareness about the environmental challenges that motivate and drive Maison Ruinart on a daily basis. The paintings also consider champagne production on a symbolic level. Like the fact that it is a living product and that it is made from a plant that grows in the ground. It is subject to the elements: to the soil, to the sky, to the weather, to the bugs that either destroy it or facilitate pollination. For me, there are may interesting metaphors there.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

There is a certain magic to it too, in which the micro organisms that make the bubbles create the critical element of the champagne. I like the idea that it is something from nothing, that it has to be kept in darkness and all these things have to happen in darkness, that they happen in a cave which is found under the ground. If you described champagne production to someone who didn’t know what champagne was, who didn’t know what wine was, it would seem like some esoteric activity.

Then, there is the idea that champagne occupies a special place within beverages, one synonymous with celebration, synonymous with luxury. This association with celebration connects it to the beginning and ending of things: the beginning of a marriage, or the end of a project. I’m interested in trying to find these metaphors, and the poetic aspect within the story of champagne.

2. What did you learn from the experience?

This collaboration has given me the opportunity to learn something about the complex process of making champagne and to make art that addresses that, to find a way to say something about that process. It is a voyage of discovery: I had no expectations, other than to learn something. The process was to visit Maison Ruinart, to speak to the cellar master, to speak to the people involved in the production so as to understand more about champagne production within the larger operation, which everyone is very passionate about. For me as an outsider—as someone who has drunk quite a bit of champagne over the years, and enjoyed it, including Ruinart – I have never thought that much about its production or how it was made.

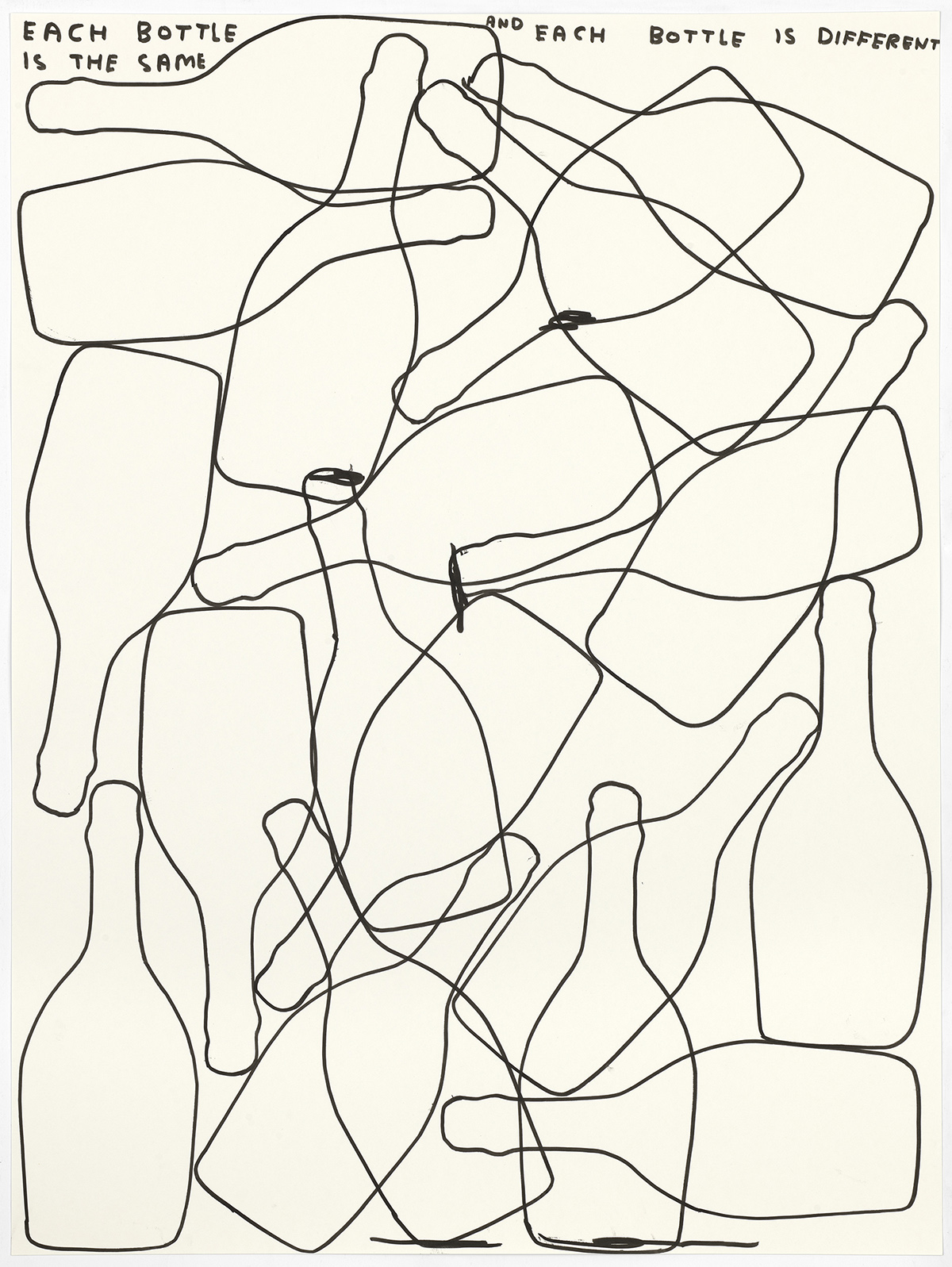

Ruinart 2020 by David Shrigley

3. Your images are often accompanied by lines of text – how does language interact with your art?

The interesting thing about working with Maison Ruinart is that it is a collaboration. It is a project whose criteria are ideal for a fine art commission. In terms of how I normally create graphic art, I start with a blank sheet of paper and my job is to fill that space with whatever comes into my head. Usually there is nothing in my head when I begin so I often write a list of things to draw: an elephant, a tree stump, a teapot, a nuclear power station etc. I have a motto: “If you put the hours in then the work makes itself”. Maybe what I mean by this is that artwork (or a least, my artwork) occurs as a result of a process. That process for me is usually to draw everything on the list. Once those things have been drawn the story has begun; more words sometimes appear; sometimes just the words on the list; sometimes more pictures; until eventually the page is full and the artwork is finished.

When I tell people about this way of making work they are sometimes impressed (sometimes not) and they say that it seems as if the work “comes from nowhere”. Having thought about this at some length, I have come to the conclusion that this isn’t the case. Art is not the creation of something new but the creation of connections between things that already exist. In this case the connection between the things on the list and the words used to describe them. But as soon as you make a statement about what art is or is not you almost immediately realise an exception to that rule.

Read more: Princess Yachts CEO Antony Sheriff on a new generation of yachting

Anyway, when making art on the subject of champagne production, one must make several visits to the champagne region. One must visit the crayères and the vineyards and the production facilities and one must ask questions of the people who work there and listen very carefully to what they say. And most importantly, you must drink some champagne. It also requires a different list of things to draw: the vines, the grapes, the soil, a bottle, a glass, the cellar master, worms, the weather etc.

One of the problems (sometimes it’s a problem) with my way of working is that when I say things through my work (the text and the image), I often don’t really know what I’m trying to say; I say it and then try to figure out what it means afterwards. Maybe it is like when a child is learning how to speak. I like to think that all artwork is a work in progress; the meaning develops and changes depending on who views the work and the context in which they view it. Meaning ferments like wine. I realise that what I am saying about the production is perhaps not what the people I have met at Ruinart would say about what they do. Maybe they might even have a problem with it. But I think it should be acknowledged that the fermentation process has only just begun and it may be some time before it is finished, if ever.

I made one hundred drawings based on my experiences of being at the House of Ruinart. The message conveyed through champagne and the brand is important. I need to start with those things. I made illustrations based on text and found a way to incorporate them into the work. But with the majority of the drawings, an image came first, and I thought about what the text should be after.

4. What role does humour play in your practice?

I guess years ago I was always keen to stress the work was incidentally funny and that I was trying to be profound and comedy was just a facet. Over the years I’ve come to realise that comedy is very important. The issue is people expect you to be funny all the time. I’m always keen to stress I’m not a comedian and I am an artist, which negates my obligation to be funny all the time. Comedy is really special and sublime. To explain why something is funny sort of pours cold water on it…

Ruinart 2020 by David Shrigley

5. How has the current global crisis affected your creativity?

I worked alone from home on smaller formats anyway so I’ve been making drawings for the last six weeks or so. I just worry about other people at the moment. Some of the work I’m producing now is influenced by the ongoing situation – or at least when I put it out there the viewer will associate it with that.

6. What do you miss?

I miss seeing friends and going to the football.

View David Shrigley’s portfolio: davidshrigley.com